There are only so many times that you can drive by an inspiring formation before you finally stop the car and just have to climb it. Smithsonian Butte looms high over Apple Valley in SW Utah and I would see it regularly coming to and from Arizona. Every time I would see it, I would just stare and wonder what it would be like to climb, what it would be like to stand on the summit. The peak boasts a very loose 5.6 pitch of climbing, an easy yet very exposed ledge traverse, and a few low fifth class steps and a ton of scrambling and route finding to gain the summit. I finally made it a priority and went for a summit bid on a cold January morning. Here is the account of Izzie’s and my climb.

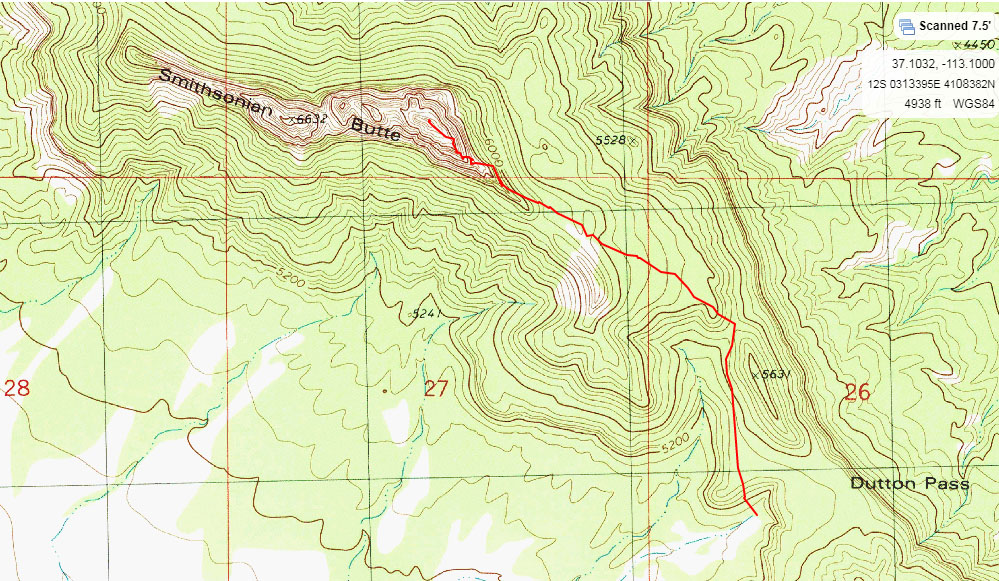

Cold and chilly the alarm blasted just before sunrise, and soon after coffee, breakfast, and feet on the ground bundled up we headed for a ridge on the southeast side of the butte. There is no real trail to the mountain so the track is a matter of choosing the best grade to the base of the climb. We side hilled, scrambled up a few cliff breaks, and gained the first step which is guarded by a canyon on the left (west) and a small hill on the right (east) as we headed north towards a low saddle. At first the going was pretty easy as we followed cattle, deer, and bighorn sheep tracks, but soon became side hilling until we finally reached the saddle. Cross country trekking is the best way to describe it, dodging cactus, loose rocks, and ankle twisters and the occasional patch of snow.

From the saddle we headed northwest through a cliff break until finally gaining the next step which was riddled with juniper trees and sheep tracks. Skirting the north side of the ridge extending south east from the butte’s exposed cliff faces we trod along through snow patches and broken rock until it was evident that skirting on flat ground would no longer be advantageous. It was time to gain elevation aiming for the most southeast cliffs protruding up from the red earth surrounding. After careful scrambling, picking through cliff bands, we found a line that worked and finally reached the south east end of the butte.

Climbing up from the saddle, finally views of the butte!

Hoof prints and side hilling towards the Butte

We skirted northwest on the base of the north face of the butte carefully trekking as we did to not fall off a drop to the north until finally finding a break where a climbable chute became evident. Still a few hundred feet below the start of the climb, we started slowly working our way up the crumbling and snow covered steps making a few class 3/4 moves, until finally we found a large ledge where we started to rope up. Roped up and ready I scrambled up into the chute which was sandy, loose, and vegetated. The climbing was easy to begin with and I stuffed in cams where I could. I slung a small sandstone column that was the size of my calf. I knocked on the column, hearing a somewhat hollow sound, hoped it would hold in a fall knowing it probably wouldn’t, and kept climbing. Up I went finding a good crack just below the crux of the route that I stuffed a BD#1 cam into . . . I kept moving it around trying to find the best placement, until finally I got the damn thing stuck! Woops, I decided to grab it on the descent, climbed up a sandy ledge which I wiped off and threw down small loose boulders to make room for a foot and mantled over. I slung another questionable sandstone column, and made some sand covered slab moves out and climbers left until finally reaching a small tree belay with left over rope from previous retreats.

Izzie soon climbed up, confirming that my cam was stuck as hell, and met me at the belay. We were still in the shade of the butte’s north face, so climbing quickly became priority. Up another 15’ and I gained a notch on the south eastern ridgeline just above a large ledge where the airy traverse awaited. Knowing there would be some hella rope drag, but not wanting to make a ton of pitches I climbed on. I traversed the airy ledge, slung a sturdy old juniper, then climbed up 15-20’ to set up a belay on a large ledge on the south side in the sun. “Belay on!” I yelled as Izzie climbed on cleaning all the gear as she went. “Wow, that’s exposed!” she said, rounding the corner and seeing the drop-off. I pulled hard on the rope, pulling it through the rope maze I’d created around the high friction sandstone corner, but soon enough she joined me at the belay.

Up and on through 4th class scrambling I found the end of the sustained rope climbing at a large tree where a rap station awaited. That tree would later be used to rappel the loose chimney we’d initially climbed up. We dropped our gear here and scrambled up the loose rising plateau. Skirting north behind a juniper, we found a slot that climbed up to the next ledge. Upon the exit, we found a 5th class scramble with a few loose blocks at the exit. Moving carefully, using a few good foot holds and finally ledges, we exited the 20’ chute with a breath of ease.

The 4th class slot that leads to the 5th class chute

5th class chimney

Continuing up a few more 4th class breaks we finally saw a small saddle that divided our ridge scramble from the final summit scramble. We down climbed, slowly worked across the loose traverse until looking up towards one loose 4th class and two 5th class obstacles. We climbed tediously on the sandy surfaces, spotting each other, finding the best line until popping out surprised to find a medium tree with webbing and a rap ring at the base. I wished I had a rope with us as I glanced back down the two short but exposed 5th class climbs we’d just ascended. But no matter, we only had 3rd class scrambles between us and the summit! “One, two, three . . . “ we chanted as we simultaneously touched the highest point of the summit with big smiles and hungry stomachs.

4th class and 5th class scrambles to 3rd class summit block

Rap tree, final 3rd class scarmable up to the summit block

Views taken in, summit registry signed (There were like 10 summit parties in the last 10 years!), and lunch consumed, we began back the way we came, down climbing all the obstacles carefully and snapping pictures of the golden peaks in the distance.

Finally we reached the tree where we had dropped our gear and got ready for the rappel. There were 2 raps, 90’ each. The first rap tree had a white 6’ rope tied to it with a rap ring. The sheath was a little sun damaged, but the inner rope core was intact. I rapped off the north side of the ridge, back into the chute to the tree which ended the top of the 1st pitch. I clipped into the rap ring connected to rope left behind at the base of the small tree. The rope there was in similar condition, sun damaged on the outside, but the core was intact. I yelled “Off rope”. Izzie soon rappelled; we collected our rope and set up the next rappel. Down I went, pausing quickly at the stuck cam with my nut tool in hand, scrubbing, pulling, and levering on the lobes until, to my relief, it finally popped free. Finishing the rap, so glad I had my cam, I was soon back on the starting ledge, and Izzie was soon to follow. Back in the butte’s shadow we collected our gear, put on our approach shoes back on (thank god), and quickly retraced our steps, down climbing and side hilling, until finally, 8.5 hours later we were back at the van headed for home. What a great day and an awesome summit!

HIKE/CLIMB INFORMATION:

- GPX Track from our climb: https://hikearizona.com/map.php?GPS=51038

- Great beta pictures from 13erGirl: http://www.13ergirl.com/smithsonian/smithsonian.html

- Outdoors with Don Gilman – Smithsonian Butte

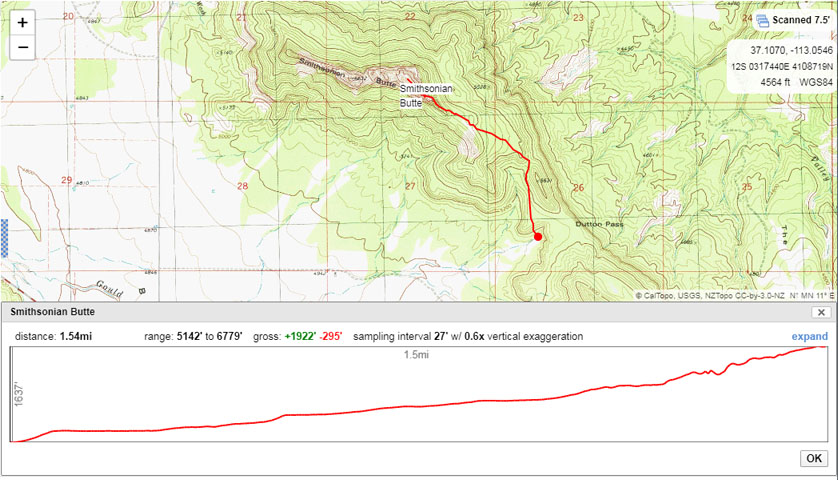

CLIMB/HIKE STATS:

- Weather: Hi 40s, Low 20s, Sunny

- Water: 2 liters

- Food: PB&J, 2 Cliff bar, 1 Nature Valley Granola bar, Trail mix

- Time: 8.5 hours

- Distance: 3 mile RT

- Accumulated Gain: 1,600 feet

- Climbing Rating: 5.6 Trad

- Number of Pitches: 2

GEAR:

- Blitz Black Diamond 28 Pack

- Black Diamond Helmet

- Black Diamond Guide Solution Harness

- 4 Black Diamond screw carabiner

- 4 Phantom DMM screw carabiner

- 6mm Accessory Chord – Anchor

- Black Diamond Camelot C4 Cams – Single Rack – 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4

- Black Diamond Offset Nut Set

- 8 Alpha Trad DMM quickdraws – Alpine draws

- Black Diamond ATC Guide

- 70 meter 9.8mm Rope

- Webbing/7mmCord for personal anchor

- 120 cm sling (x2)

- Arc’teryx Chalk Bag

- SPOT Tracker

CLOTHING:

- Smartwool Base Layer

- Wool Icebreaker Shirt

- Black Diamond Sun Hoody

- Black Diamond Wool Hoody

- Black Diamond Climbing Pants

- Darn Tough Medium Wool Sox

- Nike running shoes

- La Sortiva TC Pro Climbing Shoes